What Else Might Be Possible?

The Opportunities Hidden in Your Seemingly “Impossible” Situations

Photo by Emily Bernatt

When traditional channels close, resilient leaders don’t give up: they step outside the box, ponder what else might be possible, and ask questions that open windows to what else wants to emerge.

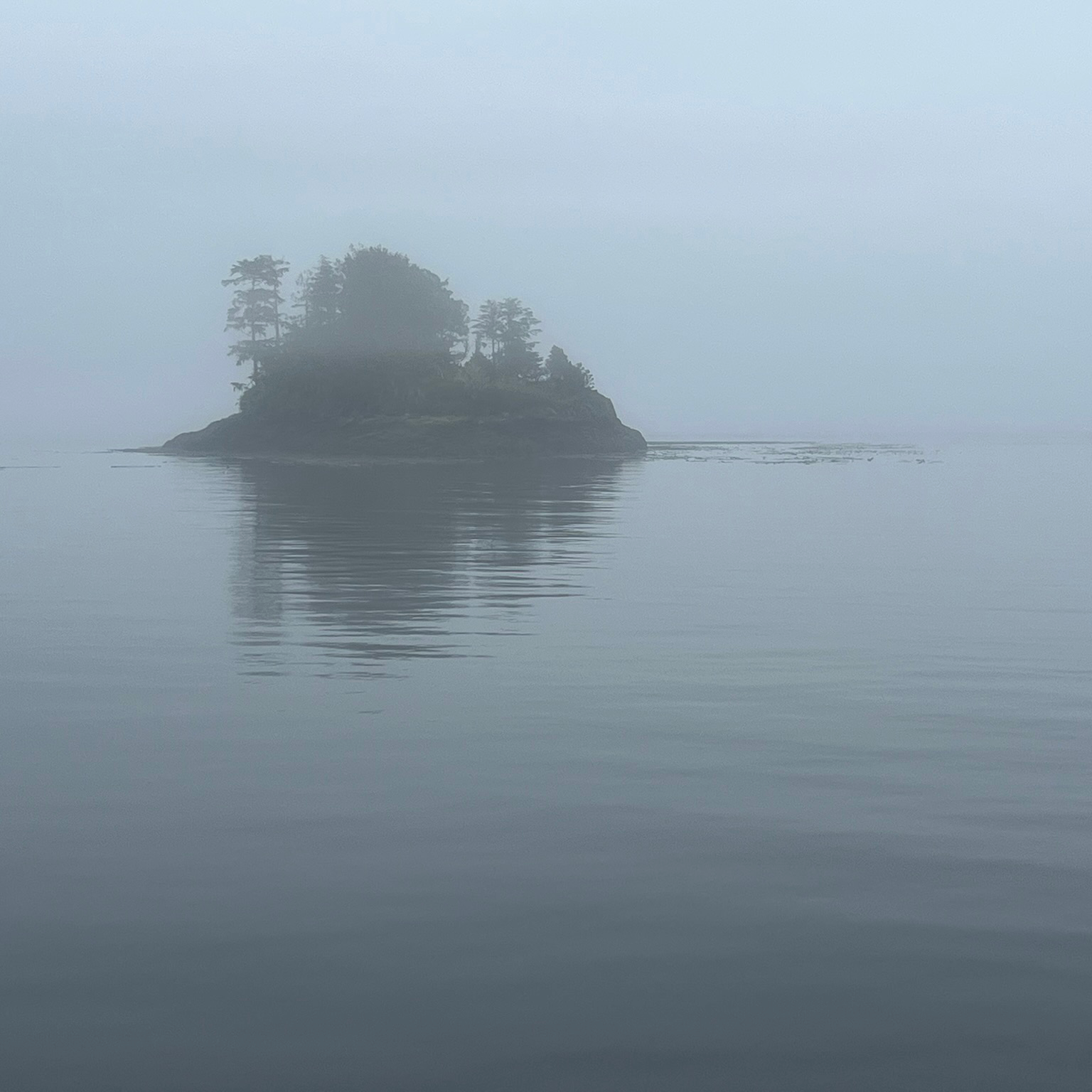

A story from Cormorant Island about fog, relationships, and the quiet authority of an elder.

Fog, Whales, and the Quiet Authority of an Elder

She longed to see humpback whales. He, orcas.

We had come to Alert Bay, in the heart of Johnstone Strait, where both gather at this time of year. I called the local whale-watching place, leaving a hopeful message about reserving three spots. Hours later, I met one of the owners: “Completely full. Only space is tomorrow afternoon.” But we were leaving on the next day’s morning ferry.

My heart sank. We were in the world’s premier location for whale watching, with dreams unfulfilled and departure looming. Every leader knows this moment: when you’ve exhausted obvious options and face the choice between accepting defeat or finding another way.

Fog and the Herons

The next morning, I rose early and walked into thick fog. Mist curled off the water, the world hushed and gray. This was my favorite time in nature, when everything was still and mysterious, my senses awake and attuned, present without expectation, simply open. In the air there was an atmosphere that awakens the dreaming of what lives just beyond visibility.

Out of that grayness came a sudden jolt of color: the fluorescent yellow of a safety jacket, moving toward me through the mist. A woman walking two dogs. I met Marilyn, an unexpected guide who would open unimaginable possibilities, the kind that leadership and life rarely offer without risk, trust, and a capacity to imagine beyond what is already known.

On the shoreline, a heron stalked for food. Like her, I too was on the hunt for breakfast.

Photo by Cathy Bernatt

I asked if anywhere might be open. She tilted her head up, visualizing the geography and location of each restaurant, said them aloud one by one, then shook her head. “It’s Sunday. Everything is closed until noon.”

We stood there for twenty minutes, talking. I told her about my niece Em’s dream to see humpbacks, and her fiancé Eric’s dream of orcas. Her expression shifted. “You need to call Porge.”

She told me about him: 86 years old, a retired Nimpkish Nation big boat fisherman, now taking people out on smaller boats. She and her husband had been welcomed by Porge as family when they moved to the island. “He’ll be awake soon,” she said, glancing at her watch. “It’s 7:57am. He usually stirs around 8:00am. You’re fine to call.”

The Call and the Invitation

At 7:58am, I picked up the phone, feeling a bit shy and hesitant to call someone I didn’t know out of the blue, yet driven by the hope of helping Em and Eric’s dream come true.

Porge answered. I explained that Marilyn had given me his number and that I was hoping he might take the three of us out: my niece, her fiancé, and me.

“Does it matter if it’s today or tomorrow?” he asked.

I learned later this wasn't a casual question. Today was meant for his annual tradition with five women who had been coming to whale watch with him for twenty years. He was weighing whether to honor that established rhythm or open it to newcomers.

“It has to be today. We’re leaving on the ferry tomorrow morning.”

“Today, then. Meet me at the dock at 9:30. My boat is green.”

Just like that, the door that had been closed swung wide.

I caught up to Marilyn farther down the road, dogs tugging at their leashes. I told her the news. She smiled wide: “Then you can’t go hungry. Come back with me. I’ll send you off with something to eat.”

In her kitchen, she toasted a thick slice of homemade sourdough, spread it with black currant jam, and handed it to me. I hadn’t eaten bread or jam in two years, but that morning I chose to receive this offering with utter delight. Food made from love for the journey, and more than food. An anchoring in relationship.

Leadership sometimes asks the same of us: to set aside protocol and accept what builds trust and connection in the moment.

Photo by Cathy Bernatt

The Green Boat

By 9:30am we were aboard Porge’s boat, named after his late wife. When I asked what the name meant, he said his wife told him it meant "the woman who walks on the beach." With a dry smile, he added, "But that's not what I think it means.”

Later, I learned a story about her name that went back in time: The name of his boat was also the Indigenous name of Ellen May Neel, a renowned Kwakwaka'wakw totem artist from Alert Bay who frequently signed her work with that name. It actually means "people come from far away to seek her advice." How fitting that people had been coming from far away to seek Porge's wisdom about these waters.

It fit perfectly. We had come looking for whales and found ourselves drawn into the orbit of someone whose presence carried steadiness, patience, and quiet depth.

Photo by Emily Bernatt

Alongside us were a group of five remarkable women, who worked or volunteered at the Sidney Aquarium. They came from different walks of life professionally, most now retired, but all bound by a deep passion for marine biology and whales. For more than twenty years, they have returned every summer to go out with Porge. They showed us what to listen for in the fog, pointed out subtle signs on the water, and, with a grin, shared their traditional baloney sandwiches. It was the only time each year that they ate baloney. It was part of their ritual that bound them to one another, and to Porge.

One of them told me the whales seemed to like the sound of his engine, the way he kept it low and steady, almost like a hum. These women had learned to trust Porge completely, following him into fog-shrouded waters because his instincts fortified a quality essential for effective leadership: knowing when the best outcomes require trusting someone who knows the territory better than you do.

At 86, Porge carried the kind of presence that comes from a lifetime on these waters. Dry humor, patience, and a way of listening, not just to people, but to tides, to engines, to fish, to whales. Being with him was like being with someone who had learned to live by listening first.

He navigated uncertainty with the patience of an elder. He paid attention to what was just beneath the surface, signals invisible to those unpracticed in listening. True leadership, I was reminded, is not about mastering uncertainty, but about how we hold our power at such times—steady enough to guide others with clarity about direction, transparency about what remains unknown, and care through the fog.

From the captain’s seat, I listened as he spoke of his grief at personal loss of loved ones; of the hard life of a fisherman, and the long years spent at sea. And he spoke about his rights as a Nimpkish Nation fisherman. Where others may be limited by regulation, his rights are different, rooted in ancestry, sovereignty, and relationship to these waters. He fishes as his ancestors did, carrying forward not only a livelihood but a lineage of responsibility. It reminded me that leadership is not only about performance, but about stewardship — honoring the traditions and communities that came before us, carrying their wisdom forward, and protecting the practices that will sustain generations to come.

What struck me was not just what he said, but how he held it: leadership here was not control or clarity. It was the art of listening, the patience to endure, and the courage to carry forward what life hands you, whether fog, grief, responsibility, or ancient tradition.

Photo by Emily Bernatt

Six and a Half Hours in the Fog

Most tours run four hours: an hour out, two hours searching, an hour back. With Porge, time bent. We left at 9:30am and returned close to 4:00pm. Six and a half hours later, we were filled with something much larger than “a tour.”

The fog kept us close, sharpening our senses. We listened for the low exhale of whales hidden just beyond sight, the splash of porpoises, the bark of sea lions. Porge showed no rush, no anxiety.

Fog teaches a different kind of leadership: when the horizon disappears, attend to what is near, what is emerging, what is right in front of you. In uncertainty, presence becomes strategy.

Photo by Cathy Bernatt

Out of the mist, the humpbacks surfaced, massive and close, porpoises dancing across their backs. Later, as the fog lifted and sunlight broke through, the orcas appeared. A northern resident pod of seven, including a juvenile, stayed with us nearly an hour, breaching, diving, resurfacing in rhythm.

Em’s dream. Eric’s dream. Both fulfilled.

The Gift of Salmon

The next morning, I went back to thank Marilyn. I brought ice cream, unsure if she and her husband could eat it. She laughed: “We eat it every night.”

She told me about helping Porge can his last catch, how he had insisted she join him, boiling and sealing jars. Then she reached up to a shelf, lifted down a heavy tin, and placed it in my hands. “Take this one with you. It’s Sockeye.”

Her bread, his boat, the whales, now this salmon. A weaving of generosity that bound us into relationship, into place.

What Remains

What stays with me is not just the whales, the bread, the salmon, but also the conversations and the care of strangers.

Leadership, on this journey, did not rest in one person. It lived in this web of connection: my willingness to keep asking; Marilyn’s generosity, problem-solving, and hospitality; the passion and loyalty of the remarkable women who returned year after year; and Porge’s patience, presence, and quiet authority. Leadership is rarely solitary. It is a constellation of small, steady acts, woven together, that make the impossible possible.

As Rumi reminds us in The Guest House: ‘Be grateful for whoever comes, because each has been sent as a guide from beyond.’ That day, Marilyn, Porge, the remarkable women, even the fog itself were all guides.

When clarity disappears and you are forced to move without knowing what comes next, it can be disorienting, lonely, even frightening. In those foggy moments, the temptation is to grasp for control, to use power as force. Yet the practice of leadership asks something different: to hold power with steadiness, to stay present in the tension, and to notice the faint signals close at hand until the next step becomes visible.

And it lives in eldership, in someone like Porge, steady in rhythm with the waters, carrying both loss and knowledge, patience and dry humor. He reminded me that leadership is not about control. It is about listening, enduring, stewarding. Sometimes it is slow, frustrating, even painful. Yet, in that practice, possibility can still surface, briefly, magnificently, before slipping beneath the waves again.

In boardrooms and strategy sessions, the fog of uncertainty is often misread as failure. But uncertainty is not the enemy of leadership. It is the laboratory where authentic leadership is forged. The task is not to eliminate ambiguity, but to lead with such presence that others will follow you into the mist, trusting that together you discover what matters most.

Final Invitation

What else might be possible in your own moments of uncertainty when you trust, open with curiosity, and honor your innate wisdom and the wisdom that surrounds you?

Acknowledgment

With gratitude to the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, and especially to the Nimpkish Nation, on whose waters we traveled and whose elder, Porge, welcomed us, I share this story in humility and respect for the wisdom of these lands, waters, and peoples, and in honor of the resilience and living traditions that continue to thrive despite centuries of attempted erasure.

Author’s note: Certain names are used with permission; others have been altered to safeguard privacy and respect the trust in which these stories were shared.